If you're looking for a generalized definition of the sanskrit word "samsara," try this: Samsara is the cyclical condition marked by birth, old age, sickness and death. In Eastern religious traditions, the only antidote to the suffering inherent in samsara -- i.e., life as most of us know it -- is the liberation of enlightenment. That idea (and many more) are woven into the fabric of director Ron Fricke's towering and meditative new movie, Samsara.

Fricke, who directed 1992's Baraka and who worked as the cinematographer on director Godfrey Reggio's landmark Koyaanisqatsi (1982), this time tries to unite his many disparate images around themes of impermanence, rebirth, death, destruction, desecration of the planet and more.

Working in 70 mm, Fricke spent more than five years filming in 25 countries. His visual feast of a film proceeds without dialogue.

The resultant "documentary" takes us to familiar and exotic locations for many different purposes. But for me, the real subject of Samsara is the photographic eye. I'm not talking only about stunning visuals, although Samsara contains a veritable glut of them. I'm talking about the way photography can decontextualize pieces of reality, presenting them in ways that feel strange, invigorating and fresh. Samsara, then, is about the power of seeing, a testament to the transformative possibilities of new vantage points.

At one point, Fricke takes us inside a massive Chinese factory where legions of workers manufacture high tech electronics. His images emphasize the dehumanizing scale of this kind of mass production. He allows us (perhaps even forces us) to come to terms with what we're observing.

And, yes, I'm writing this on a computer that probably was produced in such a factory.

As Samsara unfolds, Fricke takes his cameras to places such as the Himalayas, Jerusalem, and Mecca. In aerial night shots, cars on the freeways of Los Angeles mimic the ceaseless flow of blood cells through veins and arteries.

If there's a flaw in Fricke's approach, it involves the way he edits the movie to score worthwhile but obvious points. Desperate Brazilian favelas threaten to spill into modern downtowns, underlining a devastating social and economic split in Brazil. A chicken processing plant exposes cruel indifference to animal suffering. A section on the manufacture of ammunition is chilling.

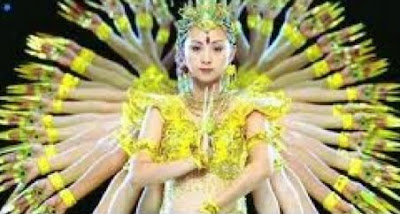

A Filipino prison, where the prisoners (as exercise?) participate in what looks like a choreographed dance fascinates while it unsettles, a combination found in many of the images in Fricke's enormous catalog of visuals.

Fricke balances his critique of modernity -- if that's what Samsara is -- with images that are as strikingly beautiful as they are mysterious. Samsara is at its best when Fricke offers the least amount of guidance, and we're left to contemplate the movie's mysterious cascade of images.

For most of the movie's 110-minute length, these images wash over us with a wavelike force that both inspires and chastens.

No comments:

Post a Comment